In the waning days of World War II, a tragedy unfolded in the Philippine Sea that would etch itself into history as one of the most harrowing tales of survival. On July 30, 1945, the USS Indianapolis, a proud heavy cruiser of the U.S. Navy, was sunk by Japanese torpedoes, plunging nearly 900 men into the shark-infested waters. For four days and five nights, these sailors fought not only the elements but also relentless sharks in a desperate struggle for life. By the time rescue arrived, only 316 survived. This is the chilling story of the USS Indianapolis shark attack, a catastrophe that stands as one of the deadliest shark encounters in human history.

A Storied Ship’s Final Mission

Before its fateful end, the USS Indianapolis was a cornerstone of the U.S. Navy’s Pacific campaign. A Portland-class heavy cruiser, it had weathered the storm of World War II with distinction. When Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941, the Indianapolis was training near Johnston Atoll. It quickly joined Task Force 12 to hunt for the Japanese carriers responsible, though the search proved fruitless. From there, the ship became a vital force in key Pacific battles, including the Battle of Attu, the invasions of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, and the Battle of the Philippine Sea. In early 1945, it supported the invasions of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, where it endured a kamikaze strike that forced it back to the U.S. for repairs.

Repaired and ready, the Indianapolis embarked on a clandestine mission in July 1945: delivering critical components of the atomic bomb “Little Boy” to Tinian Island for the bombing of Hiroshima. The mission was so secretive that most of the crew had no inkling of their cargo’s significance. Racing 5,000 miles from San Francisco to Tinian in just 10 days, the Indianapolis completed its delivery on July 26. Two days later, it set sail for Leyte Gulf in the Philippines to join the USS Idaho for the planned invasion of Japan. But the ship would never reach its destination.

The Night of Fire and Water

Shortly after midnight on July 30, 1945, Lieutenant Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto, commanding a Japanese submarine, spotted the Indianapolis in the Philippine Sea. With the war in Europe over but the Pacific still ablaze, Hashimoto seized the opportunity, launching six torpedoes. Two struck the Indianapolis with devastating precision. The first detonated in the forward magazine, unleashing a catastrophic explosion. The second hit near the fuel tanks, igniting a towering inferno that consumed the ship. Within 12 minutes, the Indianapolis sank beneath the waves, taking nearly 300 of its 1,196 crew members with it.

The surviving 900 men found themselves in a nightmare. Clinging to life rafts and debris, many were injured, burned, or coated in oil. The tropical sun beat down, and dehydration set in. Worse still, the explosion and blood in the water had attracted oceanic whitetip and tiger sharks—predators known for their ferocity. At first, the sharks fed on the dead, but soon, they turned their attention to the living.

A Living Hell in the Open Sea

The survivors’ ordeal was unimaginable. For four days and five nights, they floated in the open ocean, battling thirst, exposure, and the relentless sharks circling below. Survivors banded together in groups, kicking at the water to ward off attacks and pushing away the bodies of their fallen comrades to avoid attracting more predators. Even small actions, like opening a can of Spam, could trigger a feeding frenzy. The clear waters of the Philippine Sea offered no comfort—sailors could see the sharks’ fins slicing through the surface, sometimes dozens at a time.

“It was a bad experience,” recalled Harold Bray, a survivor, in a 2023 CBS News interview. “There was nothing good about it. Every time you looked around, somebody was gone. The sharks were there. That was a terrible scene.” Another survivor, Loel Dean Cox, described the terror to the BBC in 2013: “They’d come up like lightning to grab a sailor and pull him under. One came up and took the sailor next to me. It was just somebody screaming, yelling, or getting bit.”

The secrecy of the Indianapolis’ mission compounded the tragedy. No distress signal was sent, and when the ship failed to arrive at Leyte Gulf, no one raised the alarm. The men were left to fend for themselves, their hope dwindling with each passing day. Dehydration, saltwater poisoning, and injuries claimed lives, while shark attacks—estimated to have killed up to 150 men—added to the horror.

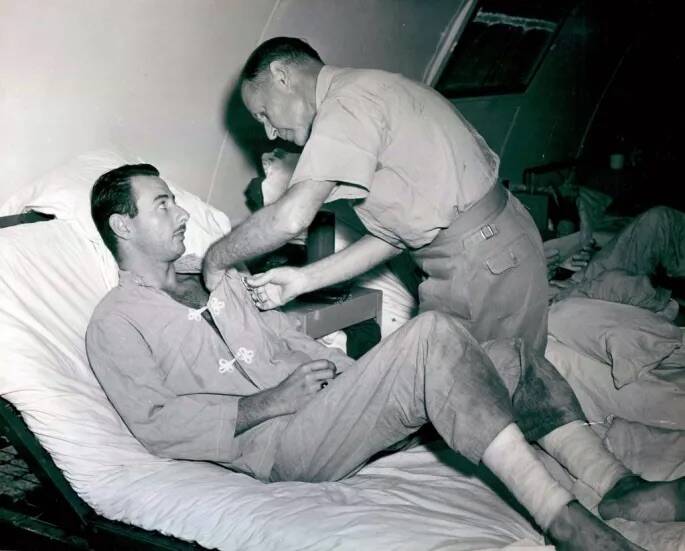

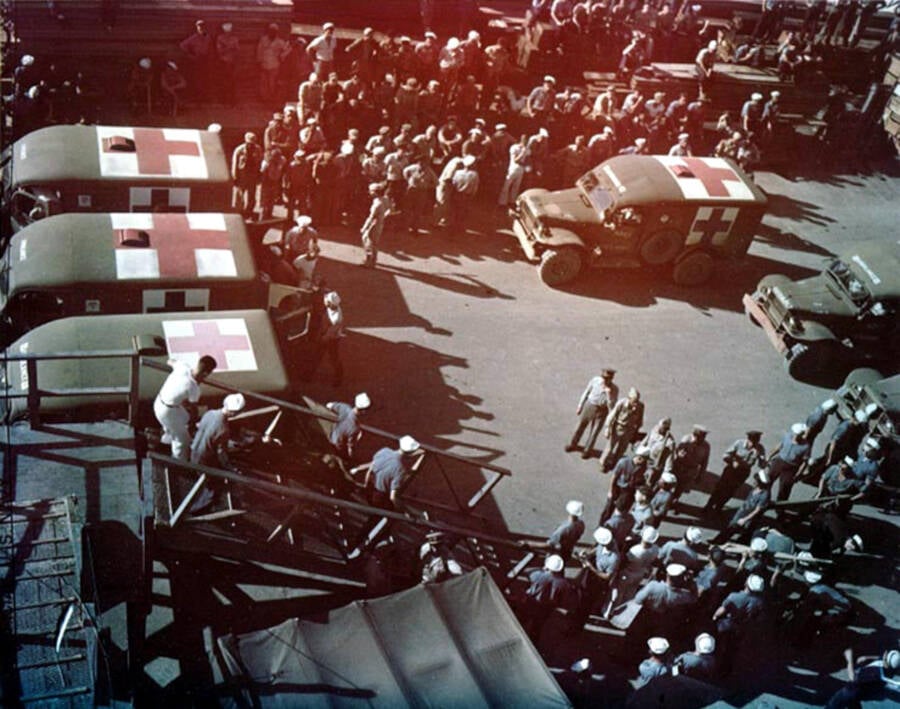

Rescue at Last

On August 2, 1945, salvation appeared in the form of a routine patrol flight. Lieutenant Wilbur C. Gwinn, piloting a PV-1 Ventura, spotted an oil slick he initially mistook for a Japanese submarine. Upon closer inspection, he saw the men in the water and alerted the Navy. A rescue operation sprang into action, with a plane arriving first, followed by a destroyer and eventually seven ships. To the survivors, the sight was divine. “It was like a strong, big light from heaven,” Cox recalled. “I thought it was angels coming.”

But the toll was staggering. Of the 900 men who survived the sinking, only 316 were pulled from the water alive. Dehydration, exposure, and shark attacks had claimed the rest, leaving a scar on the Navy and the nation.

A Legacy Tarnished and Redeemed

In the aftermath, the Navy sought a scapegoat, targeting Captain Charles B. McVay III. He was court-martialed for “hazarding his ship by failing to zigzag” and “failing to issue timely orders to abandon ship.” Yet Hashimoto, the Japanese commander, later testified that zigzagging would not have saved the Indianapolis. Despite this, McVay was convicted on the first charge. Haunted by guilt and harassed by grieving families, he took his own life in 1968. Decades later, in 2000, Congress exonerated him, acknowledging the court-martial as a miscarriage of justice.

The USS Indianapolis shark attack remains the deadliest in history, a grim chapter in a war that was nearing its end. Yet the ship’s legacy endures beyond this tragedy. Its contributions to the Pacific campaign and its role in delivering the atomic bomb components were pivotal to the Allied victory. The Indianapolis was a symbol of resilience, and its story—of bravery, sacrifice, and survival against unimaginable odds—continues to captivate and sober us today.