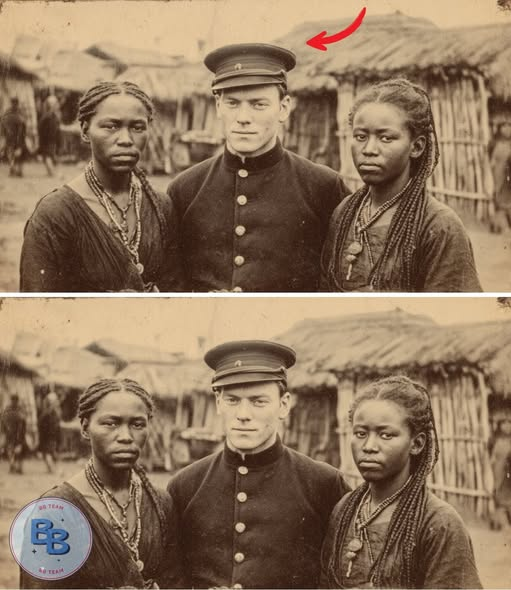

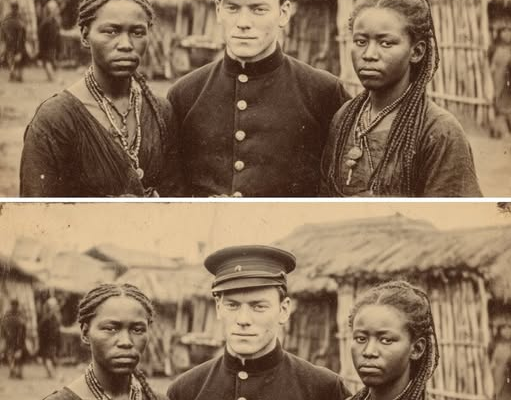

Between 1920 and 1960, thousands of Belgian colonizers arrived in the Congo. They were civil servants, engineers, single white men sent far away from their families in Europe. When they arrived, they all did the same thing.

They took an African woman into their homes to clean, cook, serve, and for something else that no one said out loud. They made them pregnant. Thousands of African women gave birth to mixed-race children, children of Belgian fathers who never recognized them. Children with lighter skin than their mothers, with the features of white men who pretended not to know them.

By 1948, there was a problem with those children. They were living proof that racial segregation did not work. They proved that “civilized” white men slept with African women they considered inferior. The Belgian state decided to solve the problem the only way it knew how. If the parents did not want those children, the state would take them by force. Like a European country, it organized the kidnapping of 20,000 children without the world doing anything.Pause

What did they do to those children after tearing them from their mothers? And what happened to them when the Congo became independent in 1960 and the Belgians evacuated en masse?

The answer lies in what began in 1948, when the first trucks arrived in the villages. When African mothers heard the engine, they knew exactly what that sound meant. And when they learned that running was useless.

The Congo was a colony of Belgium from 1908 to 1960. Fifty-two years during which Belgium extracted rubber, ivory, minerals, and wood, exploiting millions of Africans. It built its wealth on forced labor. But there were rules.

Strict rules. White people lived in their neighborhoods. Africans lived in theirs. Relationships between white men and Black women—miscegenation—were prohibited. It was officially illegal. Officially.

Because in practice, thousands of Belgian colonizers did exactly that. They took African women as concubines. They made them pregnant. They had children with them.

By 1940, there were thousands of these mixed-race children throughout the Congo. They lived with their African mothers in villages. Their Belgian fathers saw them from afar, but they never recognized them. They never gave them their last name. They were never registered as legitimate children.

And nobody did anything about it until 1948.

That year, the colonial government of the Congo created a special agency. It was called Œuvre de Protection des Métis—the Work of Protection of Métis. Its official objective was to protect children of mixed origin, give them education, and prepare them to be useful citizens.

But the truth was different.

The agency began making lists: children’s names, ages, villages where they lived, physical descriptions, and the name of the Belgian father who had never recognized them.

Before continuing, if you haven’t already, subscribe to the channel and activate the bell so you don’t miss these stories. Also, leave us a comment telling us which country you are watching from.

Henri arrived in the Congo in 1943. He was 28 years old. He was an engineer. His story was the same as that of thousands of other Belgian settlers.

What happened to him happened to thousands. What he did was done by thousands.

The mining company that hired him promised him a good salary, a big house, and the opportunity to build something important in Africa. Henri accepted without thinking much. Europe was at war. The Congo seemed like a safe place to make a fortune.

When he arrived in Léopoldville, the capital of the Belgian Congo, the first thing he noticed was the separation. White people lived in Kalina, the European quarter—large houses with gardens, paved streets, electricity, running water. Africans lived in the indigenous city—mud and zinc houses, dirt streets, no basic services.

Between the two neighborhoods, there was an invisible line that no one crossed, or at least that no one admitted crossing.

Henri was assigned to supervise a copper mine 200 kilometers from the capital. The company gave him a big, empty house. Henri lived alone, like most Belgian settlers. He had arrived single. White wives only arrived years later, once men were already established.

Meanwhile, the colonists resolved their loneliness in the same way. They hired an African woman to work at home—to clean, cook, wash clothes, and for something else that no one mentioned in public, but everyone knew was happening.

Henri hired Ansala in May 1944. She was 16 years old. She lived in a village near the mine. Her family needed money. Working for a white settler paid better than anything else.

In her words, she didn’t have many options. No African woman did.

At first, she only worked in the house. She cleaned Henri’s home, prepared his food, washed his clothes. Henri treated her the way African employees were treated: with distance, short orders, no real conversation.

But months passed. The house was big. Henri was alone. She was there every day.

And one night, Henri crossed the line that officially could not be crossed.

She was 17 years old.

There was no physical violence. There were no screams. But there was no real choice either. Henri was her employer. She depended on him to survive. When he called her to his room that night, she went, because refusing meant losing her job, losing the money her family needed—maybe something worse.

In January 1945, she discovered she was pregnant. She told Henri. He showed no surprise. No anger. He simply told her to keep working as long as she could.

Ansala worked until the eighth month. In September 1945, she gave birth in her village. It was a girl. She named her Monique.

The baby had lighter skin than the others in the village. Not as dark. She had Henri’s eyes, the shape of his nose. Anyone who saw them together could tell.

Henri never went to see Monique. He never recognized her as his daughter. He never gave her his last name. In official documents, Monique appeared only under her mother’s name. No legally registered father.

There was no connection between Henri Dubois and that light-skinned baby growing up in an African village.

But everyone knew. The mine workers knew. The neighbors knew. The other settlers knew. It just wasn’t talked about.

Henri was not the only one. In every mine, every plantation, every administrative office in the Congo, there were white men doing exactly the same thing. They impregnated their African employees. They had children with them. They never recognized them.

By 1946, there were thousands of such children throughout the Congo. They were called Métis—children who did not belong completely to either world. Too light to be considered African. Too African to be considered white.

Monique grew up in her mother’s village. She played with other children, but there was always something different. Other children looked at her strangely. Mothers whispered when she passed.

Monique didn’t understand why. She just knew she was different. Her skin was not like the others’. When she asked about her father, her mother remained silent.

Ansala tried to protect her. She taught her Kikongo, the customs of the village. She wanted Monique to feel part of the African community.

But it was difficult.

Some accepted her. Others did not. There was resentment. Monique was the daughter of a white settler. She was living proof of something no one wanted to admit, but everyone knew: white men who preached racial superiority did not practice what they preached.

Henri continued working at the mine. He kept paying Ansala to clean his house. He sometimes saw Monique from afar when Ansala brought her with her. He never spoke to her. Never touched her. Never showed interest.

It was as if the girl did not exist.

And officially, she didn’t.

Legally, Monique was not his daughter. She was just the daughter of his African employee—a problem Henri could ignore.

Until 1948.

In 1948, something changed.

The colonial government of the Congo decided it could no longer ignore the “Métis problem.” There were too many of them. They were too visible. And they represented something dangerous.

They were proof that racial segregation did not work. They were evidence that white colonists mixed with Africans they supposedly considered inferior.

The government decided it had to do something with those children. Something that would change everything. Something that Ansala and Monique would discover just a few months later.

In February 1948, the colonial government of the Belgian Congo officially created the Œuvre de Protection des Métis. In French, it meant “The Work of Protecting the Métis.” In practice, it was an agency with a single purpose: to identify all Métis children in the Congo, register them, and remove them from their African families.

The government justified this with a simple argument. Mixed-race children were being abandoned by their white parents. They lived in precarious conditions with their African mothers. They did not receive proper education. They did not learn European values. The state had a duty to protect them, to give them a better life, to civilize them.

The truth was simpler.

Those children were a disgrace. They were living proof that racial segregation was a lie. The state wanted them to disappear from public view.

The agency started its work immediately. Officials were sent to all regions of the Congo: to mines, plantations, administrative offices, and any place where Belgian settlers lived. Their job was to create lists—children’s names, ages, physical descriptions, exact locations, and the names of their Belgian fathers.

They did not need to investigate much. Everyone knew who the Métis children were. Everyone knew who their fathers were. It was a secret that no one really kept. The officials only had to write it down on official paper.

By March 1948, the lists were complete. There were 4,000 names—children between two and ten years old, living in African villages with their mothers.

The agency decided to start with the youngest. Children between two and five years old. They would be easier to separate. Easier to shape. Less able to remember their mothers later.

Ansala heard the rumors in April 1948. Other women in the village talked about it. The government was taking Métis children. Trucks were arriving in villages. Mothers were trying to hide their children. Officials came with lists and knew exactly who to look for.

Ansala was afraid. Monique was two and a half years old. She knew Monique would be on the list. There was no way she wouldn’t be.

She thought about fleeing. She could take Monique and hide in the jungle, live with relatives in a distant village, change the girl’s name, paint her skin with charcoal to make her look darker. Some mothers were doing that.

But she also knew it wouldn’t work.

The officials had complete files. They knew where every child lived. They knew their families. If she ran, they would find her. And it might be worse. She might be punished for resisting.

So she waited.

She waited because she had no other choice.

The truck arrived on a Tuesday in May. Ansala was cooking outside her cabin. Monique was playing in the dust near her.

She heard the engine before she saw it.

She froze.

The sound grew closer. Then she saw the dust rising from the road.

Ansala lifted Monique off the ground and hugged her tightly. The girl laughed. She thought it was a game.

The truck stopped in front of the cabin. Two men got down. One was Belgian—an agency official. The other was African—an interpreter.

The official held a document. He looked at Ansala. He looked at Monique. He compared her to the paper. He said the girl’s full name.

He told Ansala she had to hand Monique over. It was an official government order. The girl would go to a better place. She would receive an education. She would have a decent life.

Ansala shook her head. She said no. Monique was her daughter. She would stay with her.

The official did not argue. He did not try to convince her. He simply signaled to the truck driver.

Another man got down. Bigger. Stronger.

He approached Ansala and ordered her to release the child.

She refused.

The man grabbed Monique from Ansala’s arms. The girl began screaming, “Mama! Mama!”

Ansala tried to grab her back. The interpreter held her and pushed her away. She fell into the dust.

The men put Monique on the truck. There were other girls there—crying, screaming for their mothers.

The truck started.

Ansala stood up and ran after it, screaming her daughter’s name. She ran until her legs gave out, until she could not breathe, until the truck disappeared around the bend.

She fell to her knees. Tears streamed down her face. The dust settled around her.

Monique was gone.

She knew she would never see her again.

The truck took Monique and the other girls to an orphanage in Katanga, 600 kilometers from her village. The building was large, made of red brick, built specifically for children.

Inside, Belgian Catholic nuns were waiting.

They recorded each girl. They assigned them numbers. They cut their hair. They gave them identical gray uniforms.

The nuns spoke French. The girls spoke Kikongo, Lingala, or Swahili. They did not understand each other.

The girls cried. The nuns told them to be quiet. They should be grateful. They now had a better life.

Simone Galula arrived at the same orphanage three months later. She was five years old. Her story was the same as Monique’s.

A Belgian father who abandoned her. An African mother she was torn from. A truck. Dust. Screams no one answered.

She was placed in a room with four other girls. Wooden bunk beds. No mattresses. No sheets. One thin blanket each. The roof was zinc. During the day, the heat was unbearable. The room became an oven.

The girls sweated. They asked for water. The nuns ignored them.

The routine was strict. Wake-up at five. Mass at six. Breakfast at seven. French lessons from eight to noon. Lunch at noon. Manual labor in the afternoon—cleaning, washing clothes, cooking. Dinner at six. Mass at seven. Sleep at eight.

Any deviation was punished.

If a girl cried, she was punished.

If she spoke an African language instead of French, she was punished.

If she asked about her mother, she was punished.

The punishment was always the same: blows with a ruler on the hands, sometimes on the legs.

The nuns showed no compassion. They told the girls they were wild. That they needed to be civilized. That they should be grateful.

One night, after six months, Simone asked another girl the question she could not stop thinking about:

“Why do they hate us if we are their daughters?”

The other girl did not answer.

None of them had an answer.

They only knew they were different. Not white enough to be European. Not Black enough to be African. Trapped in a place where no one wanted them.

And they did not know that in 1960, something even worse was coming.

In 1960, the Belgian Congo was on the verge of collapse. For years, the Congolese had demanded independence. There were protests, strikes, and violence.

Finally, the Belgian government gave in.

On June 30, 1960, the Congo would become an independent country. After 52 years of colonial rule, the Belgians would have to leave.

The white colonizers packed their bags and left the country.

But there was a problem no one wanted to mention.

What would happen to the 20,000 Métis children who had been locked in orphanages over the previous twelve years?

The Belgian government discussed several options. Some officials suggested taking the children to Belgium and giving them Belgian nationality, integrating them into European society.

Others opposed the idea. They argued that bringing 20,000 mixed-race children to Belgium would create racial problems. Belgian society was not ready to accept them. It would be better to leave them in the Congo.

In the end, they made a decision that was not really a decision at all.

They did nothing.

They did not evacuate the children. They did not give them documents. They did not provide resources.

They simply left them behind.

Léa Tavares Mujinga was 14 years old in 1960. She had spent the last eight years at the Saver orphanage in Rwanda. Her father was a Belgian officer who had returned to Brussels when she was four years old. Her mother was from a village Léa no longer remembered.

She had been torn from her mother so young that her memories were blurred—vague images, sensations more than memories.

The only life she truly knew was the orphanage: strict routines, manual labor, endless masses, and the constant promise that one day, when she was “civilized enough,” she would have a better life.

In June 1960, Léa noticed something had changed. The nuns were nervous. They whispered among themselves. They packed boxes.

Léa asked the other girls what was happening. No one knew for sure, but they all felt that something big was coming.

On June 28, two days before independence, the superior sister gathered all the girls in the dining hall. She explained that the Congo would soon be independent and that the Belgian nuns would have to return to Belgium. The orphanage would close.

The girls listened in silence.

Then one girl asked what everyone was thinking.

“Are we also going to Belgium?”

The superior sister paused. Then she shook her head.

No.

They were Congolese. They would stay in the Congo. The new Congolese government would take care of them.

Léa felt something cold in her stomach.

She asked if they could go back to their mothers.

The nun said she did not have that information. The files with their mothers’ names had been lost. There was no way to contact them.

Léa insisted. She said her father was Belgian. She had the right to go to Belgium.

The superior sister looked at her with something like pity. She told her that her father had never recognized her. She had no Belgian documents. Legally, she had no connection to Belgium.

The next two days were chaotic.

The nuns packed clothes, books, religious objects—anything of value. Cars arrived constantly. Boxes were loaded. One by one, the Belgian sisters left.

Léa and the other 40 girls watched from the windows. The women who had been their only authority figures for years got into cars and disappeared.

There were no goodbyes. No explanations. No plan for the girls left behind.

On June 30, 1960, the last car left the orphanage.

Léa walked downstairs. The building was empty. Offices and archives had been looted and disappeared. Classrooms were abandoned. The kitchen had no food.

She went outside. The other girls were there. They all stared at the road where the cars had gone.

No one spoke.

What could they say?

They were completely alone. No family. No documents. No money. No food. In a country that had just been born and was already descending into chaos.

That night, they heard screams in the distance. Gunshots.

The Congo was rapidly disintegrating. The Congolese army had mutinied against its Belgian officers. Looting spread through cities. Violence filled the streets.

And in the middle of all this, forty Métis girls hid in an abandoned orphanage.

At eight o’clock that night, they heard the sound of a truck approaching.

The girls ran to hide. Some went into closets. Others hid under beds. Léa ran to the basement with five other girls.

The soldiers entered screaming. They were looking for the white nuns. They were drunk, furious.

They shouted about revenge. About years of humiliation. About everything the Belgians had done to them.

They smashed furniture. They destroyed what little remained.

Léa listened from the basement, covering her mouth so she would not make a sound. The other girls trembled beside her.

Three hours passed.

Three hours in the dark.

Three hours not knowing if they would be found.

When silence finally returned, Léa climbed the stairs slowly.

The orphanage had been completely looted. Nothing remained.

Over the next weeks, the girls tried to survive. Some searched for food. Some tried to return to their villages.

Most did not know where they came from.

They had been taken too young. They did not remember their mothers’ names. They did not know which village they belonged to.

Léa tried to obtain documents. She went to offices of the new Congolese government and explained her situation. She was told she needed a birth certificate, identity papers—something to prove she existed.

Officials asked for information about her parents.

She had none.

No father’s surname. No mother’s full name. No village of origin.

The officials shook their heads. Without that information, they could do nothing.

Léa was 14 years old and legally did not exist.

She was not Belgian because her father never recognized her. She was not Congolese because she had no documents.

She was stateless.

And there were thousands like her.

While Léa was struggling to survive in a chaotic Congo, trying to obtain papers to prove that she existed, her Belgian father was living comfortably in Antwerp.

He had a wife. He had three legitimate children. He worked as a retired officer of the colonial army and received a generous pension. He lived in a house with a garden.

His children went to good schools. They had a future. They had opportunities.

They had everything Léa would never have.

And it was not just Léa’s father. Thousands of Belgian men had done exactly the same thing. They had impregnated African women. They had allowed the state to steal those children. They had returned to Belgium. They had married white women. They had legitimate children.

They went on with their lives as if those other children—the mixed-race children abandoned in the Congo—had never existed.

But those children did exist.

And fifty years later, some of them decided it was time for Belgium to answer for what it had done.

For decades, no one talked about the Métis children. Belgium remained a respected country in Europe—civilized, democratic, a founding member of the European Union.

No one mentioned what had happened in the Congo.

Belgian history books did not include the systematic kidnapping of 20,000 children. Schools did not teach about the orphanages. Politicians did not discuss colonial policies that had separated mothers from children.

It was as if it had never happened.

As if those children had never existed.

But they had existed. And some of them had survived.

Monique Vintubengi managed to leave the orphanage at the age of 18. She worked as a domestic worker in Kinshasa for decades. She never married. She never had children.

She lived alone in a small room.

For years, she tried to find information about her mother. She went to government offices. She asked in her home village. She searched through archives.

She found nothing.

The records had been destroyed or taken to Belgium when the colonizers left.

Monique did not know her mother’s full name. She did not remember her face. She only remembered the moment she was torn from her arms.

That memory never left her.

Simone Galula had been luckier in some ways. After years of bureaucratic struggle, she managed to obtain Congolese documents. She married and had two children.

But she lived with the trauma of what had happened. Nightmares. Memories of nuns hitting her. The unbearable heat under the tin roof. Girls crying for their mothers.

Simone never told her children about her childhood. It was too painful. Too humiliating.

She carried the burden in silence, like thousands of other survivors who learned to remain quiet, to pretend everything was fine, not to ask questions about a past no one wanted to remember.

Léa Tavares Mujinga managed to reach Belgium in the 1970s. She found work as a nurse and lived in Brussels for decades.

But legally, she remained stateless.

She did not have Belgian nationality. She did not have a valid birth certificate. When she wanted to get married, she discovered it was impossible without proper documents.

Léa contacted Belgian authorities. She explained her story. She said her father had been a Belgian officer. She had been torn from her mother. She had spent years in a Catholic orphanage funded by the Belgian state.

Officials told her there were no records. Without her father’s name, they could do nothing.

How could she prove something that had been deliberately erased?

For decades, the survivors lived like this—isolated, fragmented, each carrying individual trauma, unaware that thousands of others shared the same fate.

Then, in the 2000s, something changed.

The internet allowed people separated by continents to connect. Support groups appeared. Forums and websites were created. Orphanage survivors began sharing their stories.

They discovered they were not alone.

In 2015, a group of survivors created a formal organization. They called it Métis de Belgique.

Their goal was simple: to pressure the Belgian government to recognize what had happened, to open the archives, to help survivors find information about their families, and to ask for forgiveness.

At first, the Belgian government ignored them. Officials said it was the past. Too much time had passed. Nothing could be done.

But the survivors did not give up.

They contacted journalists. They told their stories on television, in newspapers, on radio programs.

The story became public.

Belgians who had never heard of the Métis children began to learn about systematic kidnapping, orphanages, and abandonment in 1960.

Public pressure grew.

Politicians began asking questions in Parliament. Activists organized protests. The Catholic Church, which had run the orphanages, faced intense criticism.

In 2016, the Belgian Catholic Church issued an apology. It acknowledged its role in separating Métis children from their mothers, running orphanages where abuse occurred, and being complicit in a grave injustice.

But many survivors said the Church’s apology was not enough.

The Church had been an instrument. The real responsibility lay with the Belgian state—the government that created the lists, sent the trucks, and financed the entire system.

And the Belgian state had still not spoken.

In 2017, the Belgian Senate organized a colloquium on the Métis children. Survivors were invited to testify.

Monique, Simone, Léa, and others traveled to Brussels. Some entered the Parliament building for the first time in their lives.

They sat before senators and told their stories: the day they were taken from their mothers, the years in orphanages, the abandonment in 1960, decades of struggling for documents, and the endless search for their families.

Some senators cried.

The Senate President admitted she had never learned this history in school. It was a taboo part of Belgium’s colonial past, deliberately hidden.

After the colloquium, pressure mounted for official action.

In April 2018, Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel finally acknowledged what had happened. He recognized the systematic segregation of Métis children and admitted that the Belgian state had separated them from their mothers on racial grounds.

But he stopped short of calling it a crime. He called it an injustice.

In March 2019, the Belgian federal government officially apologized to the Métis children.

For many survivors, it was an emotional moment. After seventy years, someone finally acknowledged what had been done to them.

But for others, apologies were not enough.

They wanted justice.

In 2021, five women—Monique Vintubengi, Simone Galula, Léa Tavares Mujinga, Noëlle Berbèque, and Maria José Loshi—filed a lawsuit against the Belgian state.

They demanded compensation and recognition that what had been done to them was a crime against humanity.

Their lawyers argued that the systematic kidnapping of children on racial grounds met the legal definition of a crime against humanity and did not expire with time.

The Belgian state argued the opposite: that the events were too old, that they were not considered criminal at the time, and that the legal period had expired.

The court initially rejected the claim.

The women appealed.

On December 2, 2024, the answer finally came.

Chamber 31 of the Brussels Court of Appeal was full—activists, journalists, descendants of victims, and in the front row, the five women.

They had waited their entire lives for this moment.

The judge read the verdict. The court ruled that the women had been separated from their mothers before the age of seven, without consent, solely because of their mixed-race origins, as part of a systematic plan by the Belgian state.

The court concluded that these acts constituted a crime against humanity.

Monique cried—not from sadness, but from relief.

After 77 years, the truth was finally spoken.

The court ordered the Belgian state to compensate each woman €50,000 for moral damages.

It was not about the money. It was about recognition.

Outside the court, Simone spoke to journalists.

“They stole our childhood. They stole our families. They stole our identities.”

Léa added, “We are not fighting for money. We are fighting so this is not forgotten. So it never happens again.”

The ruling was historic. For the first time, a colonial state was condemned for crimes against humanity committed during colonial rule.

It forced Belgium—and Europe—to face a truth long denied.

This is that story.

The story of how thousands of Belgian colonizers impregnated African women. How the state systematically stole their children. How it abandoned them when they were no longer useful.

And how, seventy years later, five women forced an entire country to admit the truth:

It was a crime against humanity.